Ebola

One of the world's most deadly diseases.

| Quick facts | MSF's response | Current situation | Ebola in history |

Ebola is one of the world’s most deadly diseases.

It is a highly infectious virus that can cause terror among infected communities.

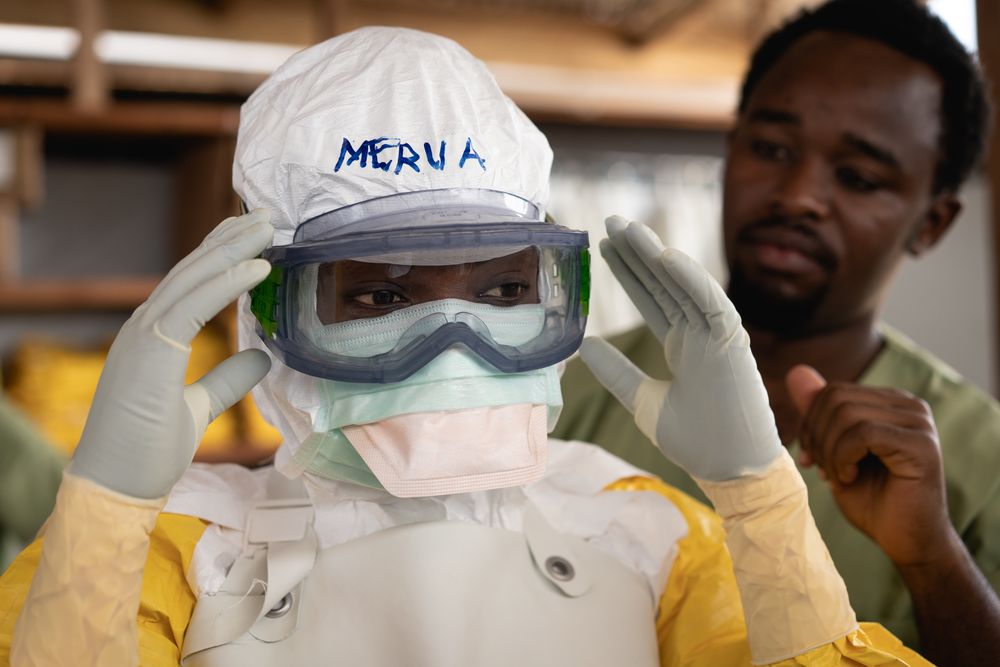

Ebola is so infectious that patients need to be treated in isolation by staff wearing protective clothing.

What causes Ebola?

Ebola can be caught from both humans and animals. It is transmitted through close contact with blood, secretions, or other bodily fluids.

Healthcare workers have frequently been infected while treating Ebola patients. This has occurred through close contact without the use of gloves, masks or protective goggles.

In areas of Africa, infection has been documented through the handling of infected chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines found dead or ill in the rainforest.

Burials where mourners have direct contact with the deceased can also transmit the virus, whereas transmission through infected semen can occur up to seven weeks after clinical recovery.

Symptoms of Ebola

Early on, symptoms are non-specific, making it difficult to diagnose.

The disease is often characterised by the sudden onset of fever, feeling weak, muscle pain, headaches and a sore throat. This is followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, impaired kidney and liver function and, in some cases, internal and external bleeding.

Symptoms can appear from two to 21 days after exposure. Some patients may go on to experience rashes, red eyes, hiccups, chest pains, difficulty breathing and swallowing.

Diagnosing Ebola

Diagnosing Ebola is difficult because the early symptoms, such as red eyes and rashes, are common.

Ebola infections can only be diagnosed definitively in the laboratory by five different tests.

Such tests are an extreme biohazard risk and should be conducted under maximum biological containment conditions. A number of human-to-human transmissions have occurred due to a lack of protective clothing.

“Health workers are particularly susceptible to catching it so, along with treating patients, one of our main priorities is training health staff to reduce the risk of them catching the disease whilst caring for patients,” said Henry Gray, MSF’s emergency coordinator, during an outbreak of Ebola in Uganda in 2012. Henry also worked on the 2014 West Africa outbreak.

We have to put in place extremely rigorous safety procedures to ensure that no health workers are exposed to the virus – through contaminated material from patients or medical waste infected with Ebola.

Treating Ebola

Standard treatment for Ebola is limited to supportive therapy. This consists of hydrating the patient, maintaining their oxygen status and blood pressure and treating them for any complicating infections.

Despite the difficulty of diagnosing Ebola in its early stages, those who display its symptoms should be isolated and public health professionals notified.

Supportive therapy can continue with proper protective clothing until samples from the patient are tested to confirm infection.

Once a patient recovers from Ebola, they are immune to the strain of the virus they contracted.

MSF contained an outbreak of Ebola in Uganda in 2012 by placing a control area around the treatment centre.

An Ebola outbreak is officially considered at an end once 42 days have elapsed without any new confirmed cases.

MSF's Response

Caring for infected patients and affected communities is crucial for a response to be effective.

MSF has intervened in almost all reported outbreaks over the past years.

Once a case of Ebola is confirmed, a swift response is vital. The needs of patients and affected communities must remain at the heart of the response, which can be defined by six main pillars: care and isolation of patients; tracing and follow up of patient contacts; raising community awareness of the disease such as how to prevent it and where to seek care; conducting safe burials; proactively detecting new cases; and supporting existing health structures.

New Ebola Vaccine

In the wake of the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola epidemic, an investigational vaccine was developed that can help control an outbreak. The vaccine is currently being trialled in an Ebola outbreak in the DRC, as part of the overall strategy to control the epidemic. MSF is vaccinated Ebola frontline workers and patient contacts in remote communities in Bikoro, Equateur Province. Participation is voluntary and the vaccine is free.

Caring for survivors

Survivors often face stigma and are ostracised from their communities. This, and the trauma of having lived through such a deadly disease, often requires counselling. People may experience ongoing physical side-effects, such as joint pain, headaches and eye problems that require treatment and follow up. MSF established Ebola survivor centres in three worst-affected countries after the West Africa epidemic.

Inside a MSF's Ebola treatment centre

Current situation

DRC Ebola outbreak, 2018 - 2019

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) declared their tenth outbreak of Ebola in 40 years on 1 August 2018. The outbreak is centred in the northeast of the country, a region recently characterised by violence and instability. The outbreak has since spread to neighbouring Ituri province, to the north.

With the number of cases passing 3,000, it is now by far the country's largest-ever Ebola outbreak. It is also the second-biggest Ebola epidemic ever recorded, behind the West Africa outbreak of 2014-2016.

The epicentre of the outbreak has moved multiple times. Beginning in the town of Mangina, the outbreak spread to the larger city of Beni, with cases now in hotspots around Butembo and the rural area of Katwa.

Ebola in history

West Africa Ebola outbreak, 2014-16

The 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa was unprecedented: 67 times the size of the largest previously recorded outbreak, it reached urban areas, and killed more than 11,300 people. Hundreds of health workers died, decimating the already-struggling healthcare systems of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

During the Ebola emergency, 28 of our staff members caught Ebola. 14 recovered but 14 died.

The vast majority of these infections were found to have occurred in the community.

On 22 December 2016, the results of an experimental Ebola vaccine trial were released by the Lancet. The trial found the vaccine to be highly effective in protecting people against the Zaire strain of Ebola.

“This vaccine will be a powerful tool to help prevent the spread of the Zaire strain of Ebola and to protect health workers," said MSF President Dr Bertrand Draguez.

"MSF will try to make use of it in any future outbreak of the disease. More research is still needed to determine the length of protection that it offers to people and into vaccines for other strains of Ebola. Progress also still needs to be made in improving the treatment of patients once they are infected with Ebola, to make sure more lives can be saved.”

Ebola in history

The Ebola virus was first associated with an outbreak of 318 cases of a haemorrhagic disease in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1976. Of the 318 cases, 280 died — and died quickly.

That same year, 284 people in Sudan also became infected with the virus, killing 156.

There are five different strains of the Ebola virus: Bundibugyo, Ivory Coast, Reston, Sudan and Zaire, named after their places of origin.

Four of these five have caused disease in humans. While the Reston virus can infect humans, no illnesses or deaths have been reported.

Before the 2014 outbreak, MSF had treated hundreds of people affected by Ebola in Uganda, Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sudan, Gabon and Guinea.

In 2007, MSF entirely contained an epidemic of Ebola in Uganda.